Resources

Access resources to support gifted learners at school and at home

On this page

Resources for Parents

Can you identify with this scenario? Art and Lily know their preschool aged daughter, Harper, is gifted. Harper has been reading environmental text and picture books since she was two. She knows her numbers past 100 and can perform simple addition algorithms. The family have incredible dinnertime conversations, where Harper’s parents are continually surprised by her advanced vocabulary. Harper also comes up with original and creative ideas. Harper’s preschool educators haven’t commented on this precociousness but despite that, Art and Lily approach their local primary school to enquire about early entry, or an acceleration missing the first year of school. After a meeting with the principal, they are stunned to learn that the school will not condone any form of acceleration of this type. The preschool educators say that Harper is emotionally immature and has poor socialisation skills. The results of psychometric testing are ignored. What is early entry? Early entry is the enrolment of a child into a state-run or independent school earlier than the state’s legislated starting age. This is an accelerative option for children with highly developed natural abilities and/or an IQ in the gifted range. Early entry requirements for different states vary, and parents are encouraged to check their local gifted organisation and/or Department of Education for more information. State policies can support early entry as an accelerative option, but the uptake of this strategy is very limited in practice. What are the benefits of early entry? Can be an effective intervention with positive academic and social outcomes for young, gifted children if policy guidelines are followed (Diezmann, Watters, Fox 2001; Robinson 2004) Often avoids the need for a more complex grade acceleration later in a child’s schooling Meets the academic and social-emotional needs of a gifted child Opportunities to learn and socialise with intellectual equals rather than aged-related classmates How should it be managed? Most states have policies or guidelines to follow. Please contact your local school and/or your State Department of Education. What alternatives can schools provide to early entry? For a child that is gifted, displays school readiness, and prefers the company of older children and adults, there is no better alternative than early entry or acceleration. Some schools may offer an enriched curriculum. If this is the case, teachers should have completed preservice education, or post graduate studies, in gifted education. Schools, preschools, and educators should continually: Provide challenge, as part of an appropriate and stimulating curriculum Gain the skills and knowledge to create optimal and flexible learning environments Create a learning environment where a child’s potential, talent and natural abilities allow themselves to be revealed Recognise a child’s strengths and interests Respond to the readiness of learners Foster curiosity, creativity, imagination, and perseverance Extend children’s thinking What are some of the characteristics of young, gifted children? Ability to learn quickly Imaginative and creative Sophisticated sense of humour Compassion Deep sense of justice Engagement with thinking and learning new skills Why is a child’s social-emotional development often misinterpreted? Many educators do not believe that gifted children have age-appropriate or advanced levels of maturity and socio-emotional adjustment. This is based on misinformation and misinterpretation. Gifted children are perceptive, and this enhances connections with intellectual peers but disenfranchises them from age peers. Educators can interpret these interactions as evidence of immaturity, when in fact frustration and boredom can lead to antisocial behaviours (Diezmann, Watters, Fox 2001) The truth is, that failure to provide early entry may adversely affect the learning and social emotional development of gifted children. References Kaplan, S., & Hertzog, N. B. (2016). Pedagogy for early childhood gifted education. Gifted Child Today Diezmann, C. M., Watters, J. J. & Fox, K. (2001). Early entry to school in Australia: Rhetoric, research and reality. Australasian Journal for Gifted Education 10(2):5- 18.

Gifted children, like all children, deserve to receive an education in line with their abilities—an education that provides them with the opportunity to reach their full potential. To support your child to help them to achieve their full potential is giving your child your voice to help them on this journey. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), along with statements from educational providers including Australia’s Mparntwe Education Declaration (Council of Australian Governments Education Council, 2019) specify the need for provision of opportunities to enable all students to achieve their full potential. Given this, it is reasonable to expect that your gifted child will be excited about and interested in school; that they will be allowed a reasonable amount of time to work with like-minded peers on material that challenges them; and will be taught by teachers who have some understanding of the needs of gifted students. What do I need to know to support my gifted child? Learn as much as you can from many sources of information; look at the websites of gifted organisations; read the policy statements from your school and education system in which your child is enrolled; find out about the common myths surrounding educating gifted children(Gifted and Talented Association of Montgomery County, 2010, Feb 24) and how to dispel these myths; investigate widely (National Association for Gifted Children, 2018) and consider attending gifted education seminars, webinars and conferences on gifted children and their education; learn some of the language and words that educators might use, and be prepared to ask them to define what they mean if you don’t understand during a meeting. Find out what education systems provide for gifted children – from opportunities such as selective schools to participating in challenges and competitions, and everything in between. How should I approach my child’s school? Start by making an appointment, let them know the subject of the meeting, how long you need and who you might like to attend the meeting with you. Try to meet the classroom teacher/s first, before meeting with the principal. Be prepared to provide background information in advance of the meeting to give the school a chance to do some preparation. This recognises the professionalism of those teachers you are meeting and reduces the need for them to respond to you without preparation. Consider whether you would like your child to attend the meeting – this will depend on a number of factors, including the age of the child, the child’s level of confidence, their capacity to verbalise their needs and the comfort level of the people you are meeting. If you think that having a support person with you for the meeting would be helpful, do not be afraid to advise that this person will also be attending. If the first meeting with the class teacher is not as successful as you would like, think about who else might be involved in a future meeting, such as: grade supervisors, the principal, a gifted education specialist, or an educational psychologist. What should I do to prepare for the meeting? Apart from knowing enough to talk confidently about your gifted child and their needs, prepare and plan your meeting. Know what you want to achieve (making sure that this matches with your child’s desires) and how you are going to put your case to achieve it. Practice at home, in front of a mirror, moderate your voice pitch – don’t shout, but don’t whisper, and know your weak points – what might be an emotional trigger and where you might need to pause for breath. Don’t be afraid of silence in your meeting while you gather your thoughts. Anticipate objections and have prepared responses – the objections will probably be the common myths and misconceptions about gifted children and their education. Don’t forget – you don’t have to do this on your own – you are absolutely able to take a support person with you, and have someone help you prepare. Find out what you can about the people you are meeting and analyse your own values and beliefs in respect of what you are advocating for. And what about in the meeting? Approach the meeting positively and build a relationship with those with whom you are meeting. Try to remain calm and speak confidently. Be prepared to identify how you want to move forward: what are you hoping to achieve for your child? What sort of time frame can you agree upon and when will you meet to follow up? You may like to request a copy of the meeting outcomes in writing and show thanks to the people with whom you met. Where can I get support? The education system in which your child is enrolled may have staff who are gifted education specialists and the school or system may have specific programs, groupings or structures for gifted students. Every school has access to above-age curriculum, whether on campus or online, and every teacher should be able to provide the right curriculum for your child, although for highly gifted students acceleration may need to be considered. All Australian states and the ACT have gifted organisations – join the one in your state so you can benefit from the support and information that they can provide. What are my options if working with the school is unsuccessful? If advocacy with the school is unsuccessful you could consider contacting those responsible for the education system in which your child is enrolled; or you could explore other schooling options, including home schooling. You may want to contact your local association for the gifted for advice and support. References Council of Australian Governments Education Council. (2019). Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration . Melbourne, Australia: Australian Government. Retrieved from http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf . Gifted and Talented Association of Montgomery County. (2010, Feb 24). Top ten myths in gifted education [Video file] . https://youtu.be/MDJst-y_ptI National Association for Gifted Children. (2018). Parent tip sheets . National Association for Gifted Children,. Retrieved 14 June from https://www.nagc.org/resources-publications/resources-parents/parent-tip-sheets United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. (1989, November 20). https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx

Is your child showing the ability to learn at a level above children of the same age? Have you ever wondered if they could have the opportunity to learn at their preferred level at school? You are not alone in thinking this. The practice of matching the level, complexity and pace of curriculum to the individual student by moving them through an educational program at a faster rate than usual, is known as acceleration (Salkind, 2008). Decades of research show that thoughtful and carefully planned acceleration benefits a gifted student academically and does no harm socially or emotionally (Assouline et al., 2015a, 2015b; Colangelo et al., 2004a; Colangelo et al., 2004b; Culross et al., 2013; Feldhusen et al., 1986). However, acceleration is often underutilised by schools, largely due to many myths and beliefs that are simply unfounded (Gifted and Talented Association of Montgomery County, 2010, Feb 24). There are many methods of acceleration (Department of Education, 2012; Ronksley-Pavia, 2011), some examples include: Grade-skipping, where one or more full grade levels are omitted, for example a student may move from grade 3 directly into grade 5 Early entrance to school, where a student begins their schooling (usually Kindergarten) at a younger age than normal Grade telescoping where students work through the curriculum of two or more grades in less than the normal number of academic years Subject-based acceleration, where a student does the work of a higher grade level for a particular subject either: In their own classroom but working on higher grade material By attending a higher-grade classroom for that subject Through dual enrolment - also enrolling in a higher level of schooling for a particular subject, e.g. studying a university subject while still in high school How do I know if grade or subject acceleration is a good choice for my child? For grade skipping, ideally you will need to have your child assessed by an educational psychologist who is skilled in working with gifted children. That person will administer an IQ test for your child and provide you with a report. The report may include recommendations for a subject acceleration or a grade skip. In general, grade skipping will require a full-scale IQ of 130 or more, with the student demonstrating advanced ability across all areas. Everyone involved - you, the school and your child should all be in favour of acceleration. In particular, the receiving teacher/s should be supportive and prepared to help the student settle into the new classroom and bridge any knowledge gaps they may have. Your child should be free of any major social and emotional problems and should be motivated and persistent in their approach to learning. Note that sometimes the school may perceive behaviour issues or failure to engage ‘normally’ with same age classmates as socially and emotionally immature and resist the idea of acceleration. The behaviour and ability to form relationships may well improve if the child is appropriately placed in a higher grade. The child should be in good health. A child’s physical size doesn't matter unless the child wishes to engage in competitive sport. A trial period in the proposed receiving year level is highly recommended to ensure the accelerated grade level is the correct placement. How many grades should a child skip? The child should be performing above the average of the class into which they accelerate. A trial process will help to clarify the appropriate placement. If the child is accelerated into a class and they are achieving at a level well above what is expected for that grade, the acceleration is unlikely to meet their needs academically, socially or emotionally. When should a grade skip take place? Ideally, at the end of a school year - but the move to the higher grade may also be considered at the end of a school term. Generally, it is advised to avoid skipping the ‘transition years’ - the years when a student may have the opportunity for student leadership roles or the first year of a new school structure that will have considerably different routines (eg, completing year 6 and year 7 are often seen as important). Will a grade skip meet all my child’s needs? Probably not! Your child may need additional acceleration - whether another grade skip or subject acceleration or more challenge provided by the classroom teacher of some subjects. Can a grade skip be reversed? A trial period of at least six weeks, with regular reviews involving all stakeholders (e.g., child, teachers, parents, senior staff, school psychologist) is recommended. If it is considered best for the child that they return to their original class, then that should happen and be supported in a positive way. How will the school decide if my child may be accelerated? The school should use an objective tool such as the Iowa Acceleration Scale to assist with making the acceleration decision. Decisions made should involve input from a team which ideally includes parents, current and receiving teachers, school leadership, educational psychologist and your child. A team approach based on solid evidence and research about the benefits of acceleration should form the basis of good decision making. Will my child benefit from acceleration? Extensive research shows that well planned and well supported acceleration for gifted students benefits those students academically in both the short term and the long term. Acceleration helps students stay engaged in school and develop essential skills to tackle more difficult learning material and cope with not succeeding the first time. Accelerated students often achieve more highly than students of the same age and ability who are not accelerated. They often achieve more highly than older students in the class into which they are accelerated. Research also indicates that accelerated students cope socially and psychologically; often gifted learners are socially and emotionally more mature than same-age students and acceleration can provide access to classmates whose interests and stages of friendship development are closer to theirs. References Assouline, S., Colangelo, N., & VanTassel-Baska, J. (2015a). A nation empowered: Evidence trumps the excuses holding back America’s brightest students (Vol. 1). The University of Iowa. Assouline, S., Colangelo, N., & VanTassel-Baska, J. (2015b). A nation empowered: Evidence trumps the excuses holding back America’s brightest students (Vol. 2). The University of Iowa. Colangelo, N., Assouline, S., & Gross, M. U. M. (2004a). A nation deceived: How schools hold back America's brightest students (Vol. 2). The University of Iowa. Colangelo, N., Assouline, S., & Gross, M. U. M. (2004b). A nation deceived: How schools hold back America's brightest students (Vol. 1). The University of Iowa. Culross, R. R., Jolly, J. L., & Winkler, D. (2013). Facilitating Grade Acceleration: Revisiting the Wisdom of John Feldhusen [Article]. Roeper Review , 35 (1), 36-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2013.740601 Department of Education, S. a. E. (2012). Gifted Education Professional Development Package . Canberra, Australia: Australian Government. Retrieved from https://www.dese.gov.au/collections/gifted-education-professional-development-package Feldhusen, J. F., Proctor, T. B., & Black, K. N. (1986). Guidelines for grade advancement of precocious children [Article]. Roeper Review , 9 , 25-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783198609553000 Gifted and Talented Association of Montgomery County. (2010, Feb 24). Top ten myths in gifted education [Video file] . https://youtu.be/MDJst-y_ptI Ronksley-Pavia, M. (2011). A report on acceleration for the gifted: What does it mean? Gifted , February (159), 8-11. Salkind, N. J. (2008). Acceleration. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of educational psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 4-8): Sage.

Resources for Parents and Teachers

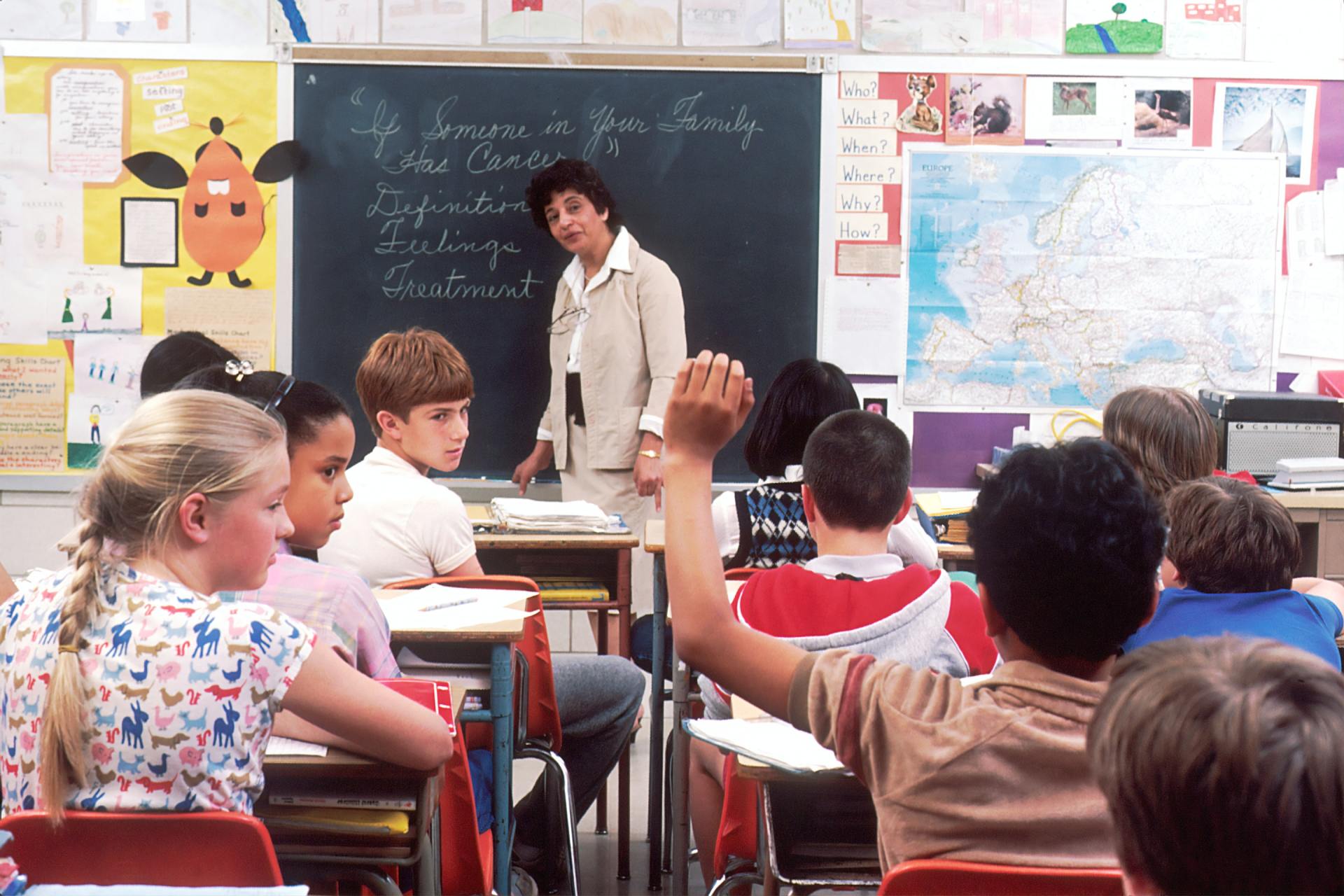

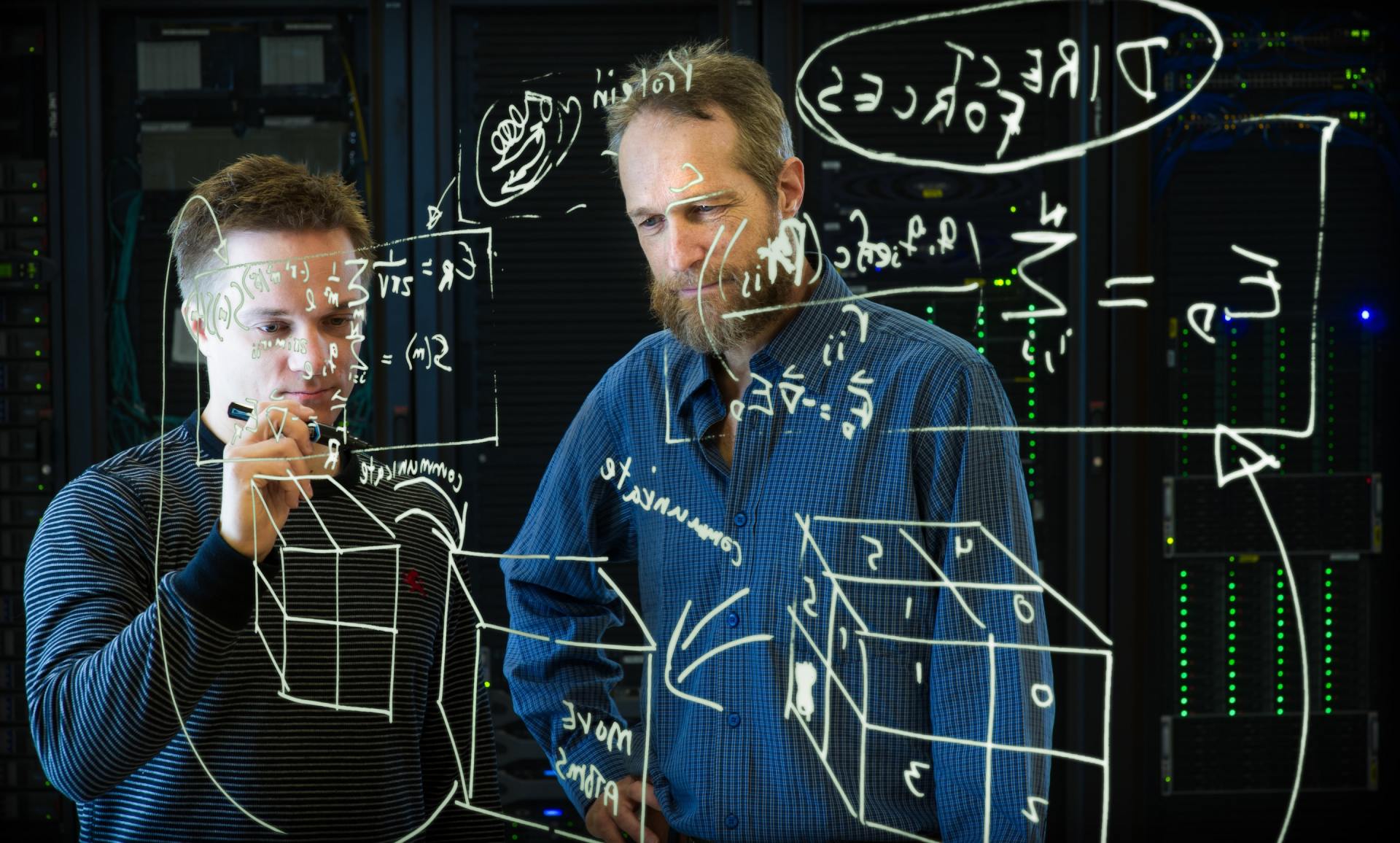

There is a vast amount of literature related to gifted students and their education. Decades of research has culminated in clear and consistent information about identification, characteristics, underachievement, strategies in the classroom, accelerative options, social/emotional needs, and how to plan appropriately challenging learning programs. Despite this, gifted students remain widely under-served, under-stimulated and demonstrate limited academic growth on school-based, standardised and national testing. Karen Rogers, in her meta-analysis of decades of research in the field of gifted and talented education, identifies five key “lessons” that describe what is consistently known and understood to be key strategies for gifted students. 1. Gifted learners need daily challenge in their specific areas of talent. 2. Opportunities should be provided on a regular basis for gifted learners to be unique and to work independently in their areas of passion and talent. 3. Provide various forms of subject-based & grade-based acceleration to gifted learners as their educational needs require. 4. Provide opportunities for gifted learners to socialise and to learn with like-ability peers (most likely not same-age peers). 5. For specific curriculum areas, instructional delivery must be differentiated in pace, amount of review and practice, and organisation of content presentation. (Rogers, 2007) The “daily challenge” message makes it clear that classroom teachers are the critical ingredient in ensuring gifted students are learning every day, and this message is reiterated within the AITSL Australian Professional Standards for Teachers Standards. Teachers of ability grouped, streamed or mixed-ability classes have strategies available to them as they are planning and implementing differentiated learning for gifted and talented students within their class. Engagement In order to maintain engagement in their education, it is important that gifted students are actually learning when they come to school each day, and see school as a place where their prior learning is recognised and new learning occurs. To ensure this happens on a daily basis, we must: Pre- and formatively assess students to determine prior knowledge and avoid students practicing and repeating skills, knowledge and understandings they have already mastered. Gifted students often experience school as a place where week after week, topic after topic, and year after year, they are asked to unnecessarily practice and repeat skills. It is important to find quick and efficient ways to find out what students know and have mastered, and to plan class and homework that introduces and builds upon new learning. Make sure students are not asked to complete ‘core’ work before they can access the work that is genuinely at their level and will offer challenge. Extension and challenge tasks that are given out after students have finished, fall into this category. A core principle of differentiation is that all students are working at their level from the beginning of a class, rather than having to ‘earn’ the work that they should be able to access from the beginning of a lesson. Gifted students often experience years of being ‘rewarded’ for completing their work by being given more, and over time they become demoralised or learn to avoid the extra work by finding ways to waste time. Avoid asking the strongest students to mentor, coach or teach other students. Teachers often do this with the rationale that this helps both students. In reality, neither the weak nor the strong student benefits from this arrangement. It is important to remember that our brightest students deserve to be learning new material rather than being a substitute teacher, just as other students expect to do every day. Gifted students enjoy and should be able to work with intellectual peers on a daily basis, in order to feel accepted, express their ideas without fear of criticism and to be appropriately challenged. Avoid asking students to catch-up on missed work if they are out of the classroom to access extension work or gifted programming. This is especially true if the missed work includes unnecessary practice and repetition! Whenever students are involved in withdrawal or pull-out programs, it is important to look for ways to assess knowledge and credit learning between the classroom and pull-out program. Gifted students enjoy learning when they can see the big picture and whole-to-part teaching works well to achieve this. Strategies such as introducing an ‘essential question’ or ‘big idea’ at the beginning of a unit of work, can increase student motivation to learn the necessary underlying skills and knowledge, and serve as a reminder to teachers to keep a focus on the high order aspects of the learning. Essential questions or big ideas must be higher order and interest can be increased by making them provocative, ambiguous and/or thought-provoking. Daily challenge There are a number of ways that teachers can offer daily challenge to students as they plan their differentiated success criteria, learning goals, resources, lessons, activities, assessments and programs. Level of abstractness – consider extending the thinking that students do, by increasing the level of abstractness. This can be done through questioning and task design, and can be a simple way to ensure students are thinking about and engaging with learning at a higher level without necessarily changing the activity or resource. Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956) is a good resource to assist with this planning, and research done by Davis and Rimm (2004) found that it is important for gifted and talented students to be working in the top three high order areas (Analysis, Synthesis, Evaluation) the majority of the time. Pace – differentiating the pace at which gifted and talented students are able to access and move through new material is vital to ensuring students are engaged and experiencing daily challenge. In order for teachers to differentiate pace, they need to be pre and formatively assessing to determine what students already know and how quickly they are grasping new knowledge, skills and conceptual understanding, with an aim to reduce the amount of unnecessary repetition and practice. Degree of complexity – making a task more interconnected with other ideas can increase the rigour of the thinking required from students. We extend students when we ask them to think about multiple ideas and the connections between these ideas, rather than asking them to engage with one idea at a time. The SOLO Taxonomy (1982) is a good resource to assist with planning this type of learning, questioning and assessment, and teachers should aim for gifted and talented students to be consistently working in the top two areas (“Relational” and “Extended Abstract”). Accelerative options – Extension, enrichment and the strategies listed above are important ways to plan appropriately challenging learning experiences for gifted and talented students, however accelerative options are equally important, if not more so. Accelerative options are any learning material that offers above-grade material or access to this material. For many gifted and talented students, there is only so much differentiation, extension and enrichment that is possible before they genuinely need to explore and learn above-level material. VanTassel-Baska and Stambaugh (2006) argue that accelerating content must be considered as a priority by teachers when planning learning experiences for gifted and talented students. Learning gain As teachers we need to ask if we have the information we need to measure the learning gain of our gifted students. If we can’t measure learning gain, it is unlikely we are offering them daily challenge and may mean they are not learning at all, even if they seem to be achieving. To ensure we can measure learning gain, we need to design our pre assessments so that we can find out the point at which students do not know material. If a preassessment is too easy and students get every aspect correct, then we have not discovered a baseline from which to plan our teaching and we will not be able to measure learning gain if it occurs. We also need to ensure our summative assessments offer enough difficulty to assess the advanced learning that students have been accessing. Implementing these strategies in no way implies that gifted students deserve more than any other student. Rather, we are endeavouring to level the playing field for these students, to provide the same degree of challenge as other students experience each day at school, to foster the same ability to persevere with tasks that are difficult, to see themselves as learners, and to experience school as a place where learning occurs on a daily basis. References Biggs, J., and Collis, K. (1982). The SOLO Taxonomy. New York: Academic Press. Bloom, B.S. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York: Longmans, Green. Davis, G.A., and Rimm, S,B. (2004). Education of the gifted and talented. University of Michigan: Pearson. Rogers, K.B. (Fall, 2007). Lessons Learned About Educating the Gifted and Talented: A Synthesis of the Research on Educational Practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(4), 382-396. VanTassel-Baska, J., and Stambaugh, T. (2006) Comprehensive Curriculum for Gifted and Talented Learners, 3rd Edition. College of William and Mary: Pearson.

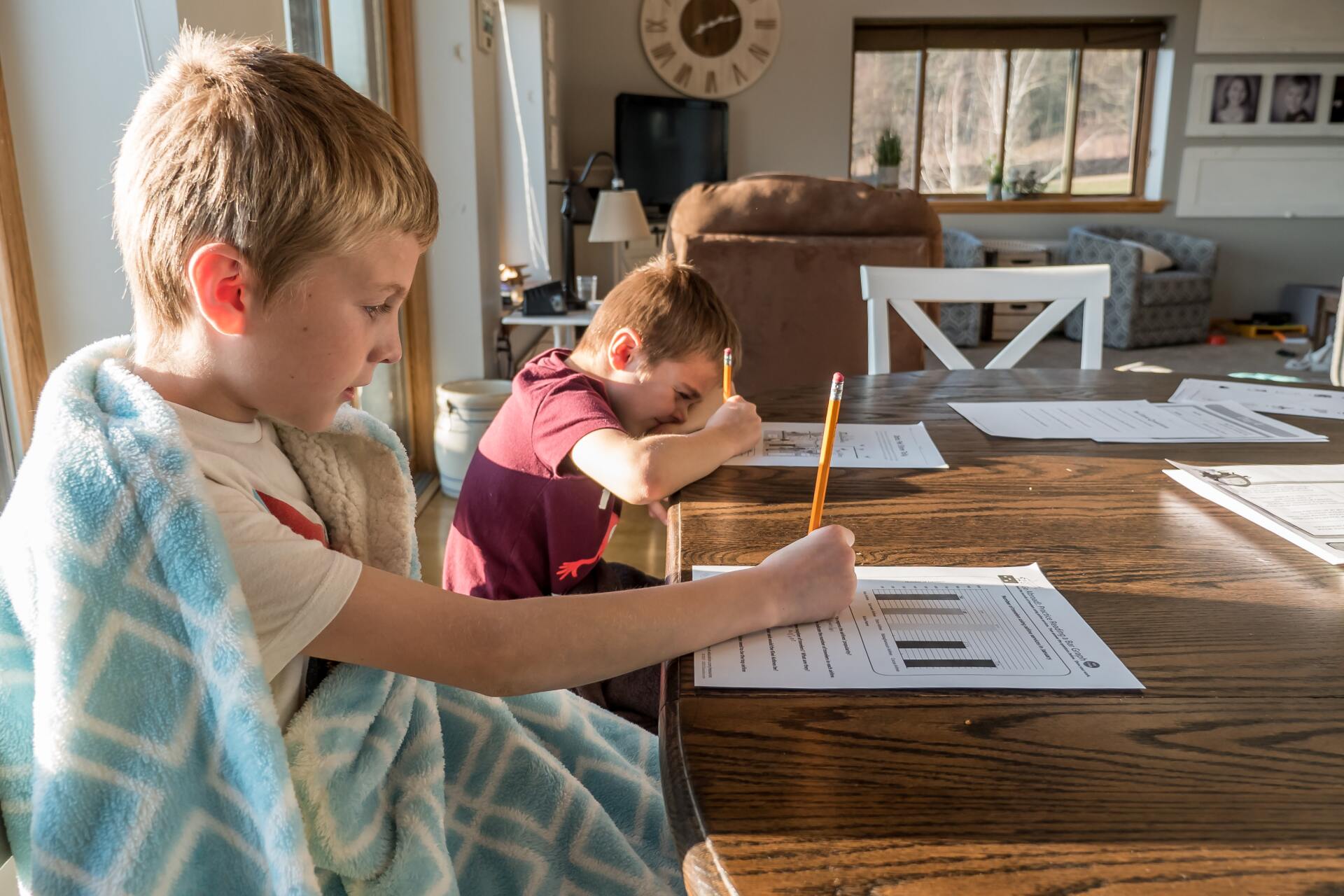

You will have students in your group or class who upon entry, will already know how to read, or have an inherent knowledge of numbers and their patterns. It is vital for you, as a teacher, to understand student mastery of concepts, which is best done through pre-assessment and talking to the student’s parents. This will guide you to plan appropriate adjustments to meet each child’s learning needs. Every student has the right to learn something new every day. A question, that you, as a teacher, can ask yourself is: Am I meeting the needs of ALL my students, or just some of them? While it is vital that teachers know their students and how they learn, this response focuses on the overall classroom learning environment. The learning environment must meet the needs of all students in an inclusive, safe, and accepting way. All student contributions should be valued and respected equally by both teachers and classmates. Play based structures are one way of meeting these needs. Activities, tasks, lessons and enrichment, for this age group, are best done incorporating play, discovery and inquiry. Consider the unit you are currently teaching. Consider the main concept and translate that to ‘big picture’ ideas. Gifted students love ‘big ideas.’ Some examples (F-2) using the Australian Curriculum HASS (Humanities and Social Sciences) units include: My personal world: Key concept Identity How my world is different from the past and can change in the future: Key concept Change Our past and present connections to people and places: Key concept Connections Science-based tasks and activities where creativity abounds, lend themselves beautifully to this ‘key concept’ scenario. This way all students can access the activity, but the gifted students will take it to a deeper level. Observe these students and create annotations, which can be used as just one identification tool. This will provide data for recommending further identification measures. You could have several activities grouped under one theme e.g., Change . Provide the activities as part of play-based choices but extend student thinking by providing provocative questions. These could be written on large cards. This provides the students with choices, which is a strategy to meet the needs of gifted students. Some examples: 1. How can we change plastic bottles so they can grow plants? (Adult supervision will be needed for cutting) Provide : plastic bottles, pictures, plants and other relevant materials. Design: Arrange plants and rocks in a way that people will be able to see them all clearly. Provocative questions: You are making a terrarium. In a terrarium you do not need to water your plants. Where will the plants get their water from? How has changing the bottle to a terrarium helping the environment? What other objects could we make out of plastic bottles? Adjustment to the core curriculum : Complexity 2. How can we change a torch into a communication device? Provide: torches, a dark space and a Morse code chart Design: Choose a word to send to a friend in Morse code Provocative questions : Invent a new method of communication. How will your new method of communication change people’s lives? Adjustment to the core curriculum: Choice 3. How can we change a paper glider to turn left or right or loop the loop? Provide: templates to make paper gliders, cardboard, plasticine, paperclips, sticky tape, scissors Design: Add weight and/or folds to change flight trajectory. Test and modify. Provocative questions: How is the way my glider flies, similar to that of birds? What makes you say that? (Provide a way to observe bird flight e.g., near a window, you tube clip) What other changes could be made to an airplane and why? Adjustment to the core curriculum: Abstraction 4. How have push/pull toys changed over the years? Provide : old and modern push/pull toys, pictures of old push/pull toys and modern push/pull toys, websites that demonstrate the push/pull action, materials to build a toy that moves Design : Invent a toy that moves. Provocative questions: How can your toy be changed to move uphill? How can your toy be changed to carry a load? Adjustment to the core curriculum: Critical and creative thinking These differentiated adjustments to the core curriculum will give you an idea of the strategies that can be employed for young, gifted children. They may be inspired by the provocative questions, or they may come up with their own. Providing open-ended activities will allow each student to shine, swap ideas respectfully and discuss collaboratively. Allow students to share their thinking and encourage their classmates to actively listen. Promote respect and awe by praising and encouraging innovation and invention in student-constructed products. These strategies will create whole class cohesion and a safe space for ALL students to thrive.

Identification of giftedness can help schools and parents determine their child’s academic and social emotional needs. Educators in the field of gifted education recommend multiple assessment strategies be used in the classroom to determine giftedness. However formal identification showing levels of giftedness, can only be administered by a registered professional. These can include school psychologists and private educational and clinical psychologists. Commonly used assessments in Australia include: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children WISC-V (Age 6 -16) Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence WPPSI-IV (Age 2 -7.7) Stanford-Binet V (Age 2 - 85+). Educational psychologists consider a gifted IQ to be 130 or higher (98th percentile) on the WISC or WPPSI, or around 132+ on the Stanford-Binet. It's important to note that the WISC and WIPPSI return different scores to the Stanford-Binet. If you need to compare different tests, you can look at the percentile score, rather than the IQ number. Levels of giftedness on the WISC-V and WPPSI-IV roughly equate to: 130+ Gifted or mildly gifted 135-141+ (or 145+ on either a verbal or nonverbal domain of the test) Highly, exceptionally to profoundly gifted 145+ Profoundly gifted IQ and levels of giftedness on the Stanford-Binet V are as follows: Moderately gifted, IQ range 130-144 Highly gifted, IQ range 145-159 Exceptionally gifted, IQ range 160-179 Profoundly gifted, IQ 180+ The challenges in administering these tests vary. They take several hours to administer and score, which makes them expensive. The verbal component scores may be impacted by culturally or linguistically diverse student groups and so they can be less effective in these individuals. They also do not measure other forms of giftedness, such as creative giftedness The strengths of these tests are that they are written for targeted age groups. They also have rigor in standardisation, rigor in the medium of measurement and consistency in administration requirements. These tests, therefore, are reliable, valid, and objective. The assessments have a long history based on large normative samples and validity has been established in multiple countries. These instruments measure both verbal and non-verbal reasoning. They are administered individually, and the reports not only give a test score but also observations about behaviours during the testing process such as levels of attention and emotional dependence. This individual administration may also reduce anxiety levels for the student.

Reading is an immersive, joyful and engaging activity which can enhance our communication and our ability to empathise and inhabit different worlds and perspectives. As an English teacher, parents often tell me: “My child HATES reading. How can I encourage them to read more? How many hours per day should they be reading?” In our fast-paced, competitive and technologically enriched world, our reading may be interrupted by social media, family members, classmates and other priorities. So, how do we encourage curiosity and wide reading and yet account for the diversity of our students and families ’lives and contexts? We can start from the simple notion: reading is everywhere . Each moment in our daily life represents an opportunity to develop our literacy, spelling, vocabulary. We read when we move around in our daily lives, stream films and series, watch the news and ponder text messages, and while we may well be frequently interrupted, the reading continues through multiple platforms as we rush through our busy days. Starting from this point, I list below some simple, practical strategies for nurturing literacy for families – students, parents and guardians. The strategies can also be useful for teachers looking to embed literacy and immersive activities across topics and disciplines. 1. Talk about words, their meaning and origin How is reading, language and the beauty of words a part of your daily life? Talking about words and thinking actively about vocabulary helps foster curiosity and develops a broad vocabulary. Whether you are watching a film, recent news or discussing your day with your family (or students in your class!), try to actively reflect on words you use in discussions. This can be as simple as your child telling you: “The teacher gave me good feedback”, and you responding, “I am so glad you found the feedback constructive”! Simply responding with a synonym or a more nuanced term will allow you to expand your vocabulary through discussion. 2. History of words: delving into Latin and Greek! Gifted students have immense curiosity about the world and different areas of inquiry. Another strategy to nurture literacy and expand vocabulary is to think about the history (etymology) of certain words we use on a daily basis and explore their Greek and Latin foundations. If your child enjoys monsters and superheroes, they may be quite keen to know what monere or super mean in Latin! Explore the most common words tied to your child’s interest and find out their history! Encouraging the joy of linguistic discoveries can turn daily conversational items into little gems of discovery which may inspire your gifted child or student and consequently build their vocabulary and linguistic proficiency. 3. Embrace the digital: on the use of apps As teachers and parents, we are also a crucial part of the learning journey – and educational applications can help us upskill (and possibly develop newfound linguistic passions!). There are numerous free and accessible apps which are basically digital versions of prominent dictionaries (Oxford, Cambridge, Merriam-Webster). Having these dictionaries on the devices you use often will make it easier to explore and discover new words and discuss their meaning. Similarly, a digital Thesaurus app can provide numerous synonyms to enrich your daily vocabulary as you communicate with your family or students. 4. Make it fun – embracing games Today’s computer games can be elaborate, enriching and engaging, creating worlds filed with educational content and potential! They can also help expand our vocabulary and provide the much-needed differentiation, acceleration and enrichment for gifted children. There are numerous simulations, adventures, strategy games and others which build language skills, including reading and writing, in a positive and engaging way. Choosing the right content and making learning fun will allow your child or students to use screen time actively and learn in the process. This is particularly important for building confidence in reading, writing and English as a subject and creating an environment where children can learn and be comfortable making mistakes! That is how we learn – and maintain that growth mindset which allows us to grow. 5. Watch films and series with English subtitles This is a simple method – when streaming your favourite films or series, use English subtitles! Most popular streaming platforms have readily available quality subtitles which follow closely what is said on the screen or effectively translate from other languages into English. Watching visual texts and following the written texts seen in subtitles can be a helpful way to include more reading into your daily routines. 6. Provide variety: reading through podcasts and audiobooks Providing multiple means of presenting information is an important aspect of inclusive education. Starting from this premise, another way to promote literacy development and motivation is to provide variety! For example, podcasts are becoming more popular than ever in our busy, fast-paced lives enriched by technology. Easily accessible on our devices, podcasts can be another great learning tool when coupled with the transcript. Most podcasts have accessibility options which include a good transcript – allowing your child / student to easily follow along! Again, pairing what is heard with what is written could also motivate and allow greater focus. Similarly, audiobooks are a great way to maintain engagement with a book – paired with a physical copy of the book or an eBook version may provide that interesting variety and alternative ways of accessing the content. 7. Build on interests and passions The final step is simple enough – we can always build on our children’s / students’ interests and passions. If the goal is to improve overall literacy, expand vocabulary, or become a more confident and adaptive communicator, building on your child’s or student’s interests can make learning fun, effective – and nurture that key ingredient needed for success – motivation! I hope you find these strategies useful – feel free to get in touch and share your own ideas and insights on supporting literacy across contexts. Dr Maja Milatovic (MA, MEd, PhD) AAEGT members can access our members area for a suggested reading list for grades 3 -6. Not a member? Find out how to become a member NB: Please note that this article only represents the views of the author(s), and is not necessarily representative of the views of the Australian Association for the Education of the Gifted and Talented.

The Australian Association for the Education of the Gifted and Talented believes that gifted learners need to be included in school and classroom planning every day of the school year. Themed days or weeks in the annual school calendar provide an opportunity to nurture, support and promote the inclusion of gifted learners. Harmony Day, Science Week, National Tree Day, Clean Up Australia Day and National Day of Action against Bullying and Violence are some examples of opportunities to be intentional about involving gifted learners. In 2021, the Australian Association for the Education of the Gifted and Talented asked three of our members who are Early Childhood Specialists to respond to the theme for Children’s Week: “Children have the right to choose their own friends and safely connect with others” These are their responses. Article 1 Children have a right to choose their own friends and safely connect with others By Elizabeth Barns The need for friendship endures across our life span, and positive relationships can have a significant effect on our wellbeing and feelings of self-worth. The skills of making and maintaining friendships begin in early childhood. These relationships usually occur with those who share our interests, and they tend to be transient and play focused. As we grow, we look for enduring friendships with those who have similar core values, personality, and interests to ourselves. Our education system, that groups children according to age, assumes that meaningful learning and friendships will most likely occur within this peer group, though as adults we understand that respectful and reciprocal relationships rarely only occur with those that are the same age as ourselves. Gifted children tend to have more mature play interests and higher expectations of friendships than their same aged peers. Hollingworth (1942) and Whitmore (1980) both identify that the gifted may have difficulty “finding peers who truly understand and appreciate their unusual and advanced perceptions” (Lovecky, 1992, p.18). They can often have more in common with older peers, both socially and cognitively, but due to limited opportunities with a diverse peer group, gifted children can be left feeling socially inadequate, frustrated and isolated. As we celebrate Children’s Week 2021, we reflect on the theme ‘Children have a right to choose their own friends and safely connect with others.’ For gifted learners this requires us to think innovatively. In order to meet the cognitive and social needs of the gifted, we need to listen to their voice and offer them choices, that include challenging opportunities that meet the child at their point of need and transcend age and grade. Gifted children are competent and capable, and provide valuable insight into their own unique needs. We need to acknowledge that children have rights and we, as the adults, have responsibilities. Providing all children, including gifted children, with positive levels of engagement and meaningful social connection with like-minded peers, is a societal responsibility that requires a more innovative and dynamic educational structure. References Hollingworth, L. S. (1942). Children above 180 IQ Stanford-Binet: Origin and development. World Book Company. Lovecky, D. V. (1992). Exploring social and emotional aspects of giftedness in children. Roeper Review, 15(1), 18-25. Whitmore, J. (1980). Giftedness, conflict, and underachievement. Allyn & Bacon. Elizabeth Barns BEd (ECh), MEd (SpEd). Member of the AAEGT Elizabeth Barns holds a Bachelor of Education (Early Childhood) and a Master of Education (Special Education including gifted). She has been an early childhood educator for more than 25 years, as a teacher and director in long day care and preschool. She has taught in vocational education and higher education for the last 15 years. She is currently an academic with a focus in early childhood, gifted and special education, and is on the committee for Gifted NSW. Article 2 Children have a right to choose their own friends and safely connect with others. By Dr Kerry Hodge Three-year-old Billy keeps to himself at preschool, which causes his educators some concern. They try to involve Billy with other children, with limited success. However, his parents are not so worried. They report that Billy is very popular as a playmate with the friends of his 5-year-old brother at home, where he successfully joins in the give-and-take of ideas as their play evolves. Billy’s situation highlights the barriers that age-based structures can create for gifted children in terms of opportunities to make and keep friends. It’s hard to have a friend if no one shares your interests, especially if the other children your age just want to run around together, while you have firm ideas about how to build a spaceship that’s going to fly to Mars. It’s no wonder that Billy chooses to sit and make intricate drawings about space exploration instead at preschool. Ability grouping, with its opportunity for like minds to become friends, is rarely an option below school age. When it does occur, as a gifted playgroup or perhaps an enrichment class, it is usually in the community and only once a week. However, friendships can develop there, especially if families of compatible children choose to get together informally outside the scheduled times. What options do early childhood educators have? Preschools and childcare centres must comply with mandated adult-to-child ratios based on age. This influences structures that make children’s movements between age groups tricky. Some early childhood settings meet regulations through ‘family groupings’ where ages are mixed and younger and older children spend most of their time together. In this structure, younger gifted children can easily choose to associate with children who offer a better social match, and age barely matters for the children involved. Of course, the oldest children cannot gravitate ‘upwards’, but they may emerge as leaders for younger children willing to be led in play scenarios at times. Most settings separate age groups. Different rooms for the ‘fours’, ‘threes’, ‘twos’ and babies works well for many children, perhaps with some mixing outdoors. For a gifted child like Billy, some flexibility is required. If there is a ‘like mind’ in the older group whom Billy could spend time with, he could gain some companionship while playing at a satisfying level of complexity. A bonus is motivation to practise his social skills in order to retain this friendship. If this arrangement works well and numbers permit, Billy could move permanently to the older group. The drawback from this ‘grade-skip’ is that eventually a decision must be made about the following year. Could Billy be allowed early entry to school, or must he ‘repeat’ a year in the four-year-olds’ room? This could be a return to the earlier mismatch unless some of his age peers have matured significantly! As happens with older ages, acceleration is not viewed favourably by most early childhood educators. Social and emotional reasons are commonly cited against early entry, even when the child clearly is intellectually ready for the school curriculum. There is a tendency for educators to assume that a child, like Billy, who plays alone is lacking social skills and to recommend another year of preschool or childcare while their social skills develop. It is important that educators find out from parents about the child’s friendship choices outside the early childhood setting. A child who seeks and is accepted by older children in the extended family or neighbourhood is certainly ready to meet the wider world of school and have access to a wider pool of potential friends. Gifted young children are in good hands when their early childhood educators understand their social needs, communicate well with families and find ways to promote opportunities for access to children who could become their friends. Kerry Hodge PhD. Member of the AAEGT Dr Kerry Hodge has worked in early childhood education as a teacher, consultant, lecturer and researcher, with a particular focus since the 1990s on the education of young gifted children. In 2009 she was awarded a Churchill Fellowship to investigate overseas programs for gifted preschoolers and teacher training in early gifted education. Kerry is currently an Adjunct Fellow in the School of Education at Macquarie University in Sydney. Article 3 Children have a right to choose their own friends and safely connect with others By Dr Rosalind Walsh Childhood is the only period of our lives when it is assumed that our friends will be people whose birthdays fall within 18 months of our own. Well-meaning early childhood educators have often promoted “we’re all friends at preschool”, failing to realise that this takes away choice from young children, and forces them to like everyone who happens to share a classroom with them. The situation can be even more fraught for young intellectually gifted children whose conceptions of friendship can be more advanced than their same age peers. In the early childhood years most children find friends based on similar play preferences. “You like cars. I like cars. Let’s play cars together.” For most children, the fact that they are at similar developmental stages would tend to suggest that they will have similar interests. However, this is not true for all children and particularly not true for children with advanced development. Finding a like-minded peer to play chess with in preschool is going to be a stretch. And may well lead to frustration when age peers find it difficult to understand complex rules. This may lead to emotional outbursts from a gifted child who can’t comprehend how their age peer can’t grasp that the knight moves in a particular way. In turn this can lead to a perception that young gifted children are emotionally immature, when in fact, what we are seeing is a child coping with a mismatch between their intellectual and social-emotion skills. Imagine explaining to a colleague, over and over again how a process works, only for that colleague to stare at you blankly. It would be hard enough for an adult to understand and handle sensitively. Now imagine a four year old in this situation. Grouping children by age has always been a matter of convenience (babies need to sleep at a certain time, play materials may not be safe for younger children etc.). Some enlightened early childhood services have moved away from age-based grouping to allow siblings to interact and children to find like-minds and friends across a whole setting. For some gifted children, their closest intellectual peer may be the teacher. Other gifted children sense their own difference from a young age and are attracted to other children who don’t appear to fit in, making friends with other children who may have been sidelined from the dominant peer-group. What we know from decades of research in gifted education is that finding a ‘true’ friend is often a gifted child’s highest priority. We all want someone to understand and value us. We also know that gifted children tend to make friends with older children, which is why it is so important that children have access to a range of age mates. We also know that healthy social-emotional development depends on having at least one good friend. Often schools will split up children who are very close, hoping that this will encourage them to make more friends, when in fact that one good friend is all that the child needs. I get on with the people I work with. I appreciate their variety of talents and their dedication. This doesn’t mean I want to invite them over for dinner and hang out on a Friday night. Nor do I restrict my friendship group to all those who happen to be turning the same age as me this year! We need to learn to be kind to everyone, but we certainly don’t need to be friends with everyone, and children have the right to choose their own friends. What can educators and parents do? Don’t assume that children will only make friends with others of the same age. Allow and encourage cross-age friendships. Provide opportunities for children of different ages to mix. Community playgroups allow for children 0-5 to mix together. In later years, community groups such as Girl Guides and Scouts have groups that operate over a range of ages. Allow flexibility with age-based rooms in early childhood setting. Provide communal space in early childhood settings where child of all ages can mix. Provide invitational curriculum opportunities where children, regardless of age, can take part based on their intellectual development. Recommended reading Gross, M. U. M. (2002, May). ‘Play partner’ or ‘sure shelter’: What gifted children look for in friendship. SENG Newsletter, 2(2), 1–3. Retrieved November 24, 2010 from http:// www.sengifted.org/articles_social/Gross_ PlayPartnerOrSureShelter.shtml Grant, A. (2013). Young gifted children transitioning into preschool and school: What matters?. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 38(2), 23-31. Shore, B. M., Chichekian, T., Gyles, P. D., & Walker, C. L. (2018). Friendships of gifted children and youth: Updated insights and understanding. The Sage Handbook of gifted and talented education, 184-195. Rosalind Walsh PhD. Member of the AAEGT Rosalind completed her PhD at Macquarie University’s Institute of Early Childhood. Her research focused on how young gifted children answered higher order thinking questions during picture book reading. NB: Please note that these articles only represent the views of the author(s), and are not necessarily representative of the views of the Australian Association for the Education of the Gifted and Talented.

Resources for Teachers

Acceleration is an educational intervention that moves students through an educational program at a faster rate than usual or younger than typical age (Salkind, 2008). Acceleration involves matching the level, complexity and pace of curriculum with the readiness and motivation of the student and will assist in ensuring gifted learners become “confident…successful lifelong learners” (Council of Australian Governments Education Council, 2019) . It is vital to ensure that acceleration, of whatever type, is something that the student desires. There are many methods of acceleration (Department of Education, 2012; Ronksley-Pavia, 2011). Some examples include: Grade-skipping, where one or more full grade levels are omitted, for example a student may move from grade 3 directly into grade 5 Early entrance to school, where a student begins their schooling (usually Kindergarten) at a younger age than normal Grade telescoping where students work through the curriculum of two or more grades in one academic year Subject-based acceleration, where a student does the work of a higher grade level for a particular subject either: In their own classroom but working on higher grade material By attending a higher grade classroom for that subject Through dual enrolment - also enrolling in a higher level of schooling for a particular subject, eg studying a university subject while still in high school Extensive research has demonstrated that acceleration is an effective and appropriate method to cater for gifted students academically, socially and emotionally (Assouline et al., 2015a, 2015b; Colangelo et al., 2004a; Colangelo et al., 2004b). Acceleration Frequently Asked Questions: Is acceleration pushing a child and therefore stressful to them? Acceleration allows gifted students the opportunity to learn at a pace that is more suited to their natural rate of learning. Where the pace of learning does not match the student’s needs, they may display disengagement, school refusal, behaviour problems, and/or mental health problems. Mismatched learning pace also denies students the opportunity to learn how to address intellectual challenges and develop resilience to cope with a degree of failure. Should we accelerate students when it did not work for “insert name here”? Every gifted student is different. There are many forms of acceleration and just because a certain type of acceleration did not work for one gifted student does not mean it won’t work for any other gifted student. One method to explore a child’s suitability for grade acceleration is the IOWA Acceleration Scale (Ronksley-Pavia, 2011). If a grade skip is recommended, the student’s teachers and parents need to dedicate time to support a smooth transition. Successful acceleration relies upon collaboration between school, home and student; appropriate selection of acceleration type; sufficient accelerative intervention; and sufficient support, including with transition. Does the Australian Curriculum allow for gifted students to accelerate through content at their own rates? Every student is entitled to rigorous, engaging and enriching learning experiences across all areas of the curriculum. Pre assessment is critical to ensure that learning area content is aligned with the learning needs of the student. The Australian Curriculum and instruction should be adapted in response to the needs of gifted students to provide flexibility in learning progression instead of rigid, age-graded academic placement. Does acceleration mean a child will have gaps in their learning? Students are accelerated because they are well ahead of the age-peers in their academic development and knowledge. Gifted students learn swiftly, and any gaps quickly disappear. Is it unfair to allow some students to accelerate? Great schools ensure that all students are catered for at their point of need. Research shows that forms of acceleration are necessary for some gifted students. Acceleration is often their best chance for an appropriate, challenging education (Waterloo Region District School Board, 2013, Aug 24). Gifted children are entitled to reach their potential, like any other children. How will a student’s social and emotional development be affected? The overwhelming research on grade acceleration has found that where academic, social and emotional maturity is identified, students will actually benefit socially and emotionally from the acceleration (Neihart, 2007). For many bright students, acceleration provides a better personal maturity match with classmates. Gifted students may feel increasingly disconnected with their same-age peers. Therefore, it makes sense to place students in a classroom where they can learn with their academic peers. Won’t the other students in the class lose their role models? Research shows that average or below average students look to those marginally above their ability level in the class as role models. Watching or relying on someone who is expected to easily succeed at a high standard does little to increase a struggling student’s sense of self-confidence. Similarly, gifted students benefit from classroom interactions with peers with similar potential and become bored, frustrated, and unmotivated when unable to work within their zone of proximal development (Gifted and Talented Association of Montgomery County, 2010, Feb 24). References Assouline, S., Colangelo, N., & VanTassel-Baska, J. (2015a). A nation empowered: Evidence trumps the excuses holding back America’s brightest students (Vol. 1). The University of Iowa. Assouline, S., Colangelo, N., & VanTassel-Baska, J. (2015b). A nation empowered: Evidence trumps the excuses holding back America’s brightest students (Vol. 2). The University of Iowa. Colangelo, N., Assouline, S., & Gross, M. U. M. (2004a). A nation deceived: How schools hold back America's brightest students (Vol. 2). The University of Iowa. Colangelo, N., Assouline, S., & Gross, M. U. M. (2004b). A nation deceived: How schools hold back America's brightest students (Vol. 1). The University of Iowa. Council of Australian Governments Education Council. (2019). Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration . Melbourne, Australia: Australian Government. Retrieved from http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf . Department of Education, S. a. E. (2012). Gifted Education Professional Development Package . Canberra, Australia: Australian Government. Retrieved from https://www.dese.gov.au/collections/gifted-education-professional-development-package Gifted and Talented Association of Montgomery County. (2010, Feb 24). Top ten myths in gifted education [Video file] . https://youtu.be/MDJst-y_ptI Neihart, M. (2007). The socioaffective impact of acceleration and ability grouping: Recommendations for best practice. Gifted Child Quarterly , 51 (4), 330-341. Ronksley-Pavia, M. (2011). A report on acceleration for the gifted: What does it mean? Gifted , February (159), 8-11. Salkind, N. J. (2008). Acceleration. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of educational psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 4-8): Sage. Waterloo Region District School Board. (2013, Aug 24). John Hattie challenging all students [Video file] . https://youtu.be/4ivNbPo6QSU

Gifted children, like all children, deserve to receive an education in line with their abilities - an education that ensures “that young Australians of all backgrounds are supported to achieve their full educational potential” (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority, 2020, p. 6). This mandate is also provided for within the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). Fortunately, there are a wide range of strategies teachers can implement in classrooms to assist their students to flourish. It is reasonable to expect gifted children within your classrooms will be excited about, and interested in school; they should be allowed a reasonable amount of time to work with like-minded peers on material that challenges them; and they should be taught by teachers who have an understanding of the needs of gifted students. What do I need to know to support gifted children in my classes? Learn as much as you can about gifted students from many sources of information; meet with the child’s family from the outset and work with them as trusted partners in the journey. Look at the websites of gifted organisations; read the policy statements from your school and education system; find out about the common myths surrounding educating gifted children and how to dispel these myths (Gifted and Talented Association of Montgomery County, 2010, Feb 24); investigate widely (National Association for Gifted Children, 2018) and consider attending gifted education seminars, webinars and conferences on gifted children and their education; familiarise yourself with the language and terminology surrounding gifted education, and unpack what the implementation of best practice research findings should look like in your classroom. Actively seek out what your education system provides in the way of support for gifted students – from selective schools or programs for gifted students to opportunities for participating in challenges and competitions, and everything in between. What should I do if I suspect a child in my class is gifted? You may have noticed a student in your class who demonstrates a quick propensity to learn or appears to be disconnected from the learning despite having ability. There are a range of checklists that may assist to identify whether this student may be gifted. From this point you may utilise a range of standardised assessments, including above level testing, to more accurately pinpoint the current level of understanding. Alongside this, talk with the school’s gifted education coordinator, principal, education system gifted education personnel, and most importantly with the student’s parents or carers. Then, to move the process forward, refer to an educational psychologist for further assessment. How should I approach teaching a gifted child? Pre-test to find out the existing level of knowledge and capability for all learning to inform appropriate planning and teaching. Plan to deliver learning at the appropriate level and pace to match the child’s capability and needs. Personalised curriculum needs to be both challenging and scaffolded ensuring students are taught the required skills and knowledge to enable them to work within their zone of proximal development (Eun, 2019; Vygotsky, 1978). Differentiate content, process, product, learning environment with differentiated task design, ensuring it is learner-centred.(Maker, 1982a, 1982b; Maker et al., 1996) Ensure opportunities for extension (within the curriculum) and enrichment (outside the curriculum). Facilitate access to intellectual peers at least part of every day (Rogers, 2002). Use appropriate acceleration - see AAEGT acceleration document for more information. Ensure a safe environment: physically safe (especially from bullying); emotionally safe, and intellectually safe to share ideas that may be different from yours and their classmates. Remember: Every child has the right to learn something new every day...and to make at least one year’s progress in every calendar year (Winebrenner, 2000) . Where can I get support? Your school or education system may have staff who are gifted education specialists and your school or system may have recommendations for specific programs, groupings or structures for gifted students. All Australian states and the ACT have gifted organisations – join the one in your state so you can benefit from the support and information that they can provide. Final Thoughts Share your knowledge and successes with colleagues. Create networks within your school, to ensure gifted students are catered for in all classes, not just yours. Celebrate your students’ achievements and treasure the journey! References Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2020). The Shape of the Australian Curriculum . Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority Eun, B. (2019). The zone of proximal development as an overarching concept: A framework for synthesizing Vygotsky's theories [Article]. Educational Philosophy & Theory , 51 (1), 18-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2017.1421941 Gifted and Talented Association of Montgomery County. (2010, Feb 24). Top ten myths in gifted education [Video file] . https://youtu.be/MDJst-y_ptI Maker, C. J. (1982a). Curriculum development for the gifted [Non-fiction]. Aspen Systems. Maker, C. J. (1982b). Teaching models in education of the gifted . Aspen Systems. Maker, C. J., Nielson, A. B., & Maker, C. J. (1996). Curriculum development and teaching strategies for gifted learners (2 ed.). Pro-Ed. National Association for Gifted Children. (2018). Parent tip sheets . National Association for Gifted Children,. Retrieved 14 June from https://www.nagc.org/resources-publications/resources-parents/parent-tip-sheets Rogers, K. B. (2002). Grouping the gifted and talented: Questions and answers. Roeper Review , 24 (3), 103-107. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. (1989, November 20). https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Mental Processes . Harvard University Press. Winebrenner, S. (2000). Gifted students need an education, too. Educational Leadership , 58 (1), 52.

Units of Work for Teachers

Resources

The following resources are available for purchase. However, if you are a member, you can download most of them free via the Member's Area.

Not sure how to login?

See further instructions here

FAQs

AAEGT's Australasian Journal of Gifted Education

A key resource for members

The Australasian Journal of Gifted Education is the official scholarly peer-reviewed publication of the Australian Association for the Education of the Gifted and Talented (AAEGT).